Aquamarine generally exhibits a weak to moderate blue fluorescence under long-wave ultraviolet light, though its response depends heavily on impurities and structure. The key insight to remember is that fluorescence isn't a universal trait - its presence varies based on geological history and can actually help distinguish natural stones from certain synthetics.

When exploring whether aquamarine glows under UV light, many encounter conflicting claims - some sellers might emphasize dramatic glowing properties while others dismiss UV reactions entirely. Others may confuse this with phosphorescence or mistake surface reflections for true fluorescence. This guide systematically breaks down UV reactivity from mineral science to practical testing, separating common assertions from verifiable facts. We'll examine specific structural factors at play and provide actionable methods for assessing any aquamarine yourself.

A common assumption is that UV fluorescence presents as a simple yes-or-no property. This stems from dramatic online images showing minerals "glowing in the dark," leading people to expect equally vivid displays in gems like aquamarine. First-time testers often become frustrated when their specimen doesn't light up like a neon sign, thinking this indicates artificial material or poor quality.

In reality, fluorescence manifests on a continuum influenced by crystalline architecture. The phenomenon results from electron transitions within activators like Fe₂⁺/Fe₃⁺ ions triggered by specific UV wavelengths. Trace elements must absorb just enough energy to excite electrons without immediately releasing all energy as heat. This delicate balance typically produces an ethereal glow rather than intense luminescence.

When evaluating stones, begin by considering the geological context: Aquamarine forms in pegmatite environments where impurities vary significantly. Next, use 365nm long-wave UV sources which tend to produce more observable reactions than short-wave. Notice that weak blue emissions still qualify as fluorescent - adjust expectations based on mineralogical reality rather than marketing depictions.

Many wonder whether this popular blue beryl variety exhibits any notable UV response at all. The question becomes particularly relevant when collectors hear conflicting reports about aquamarine's luminescent behavior compared to minerals like fluorite or diamond.

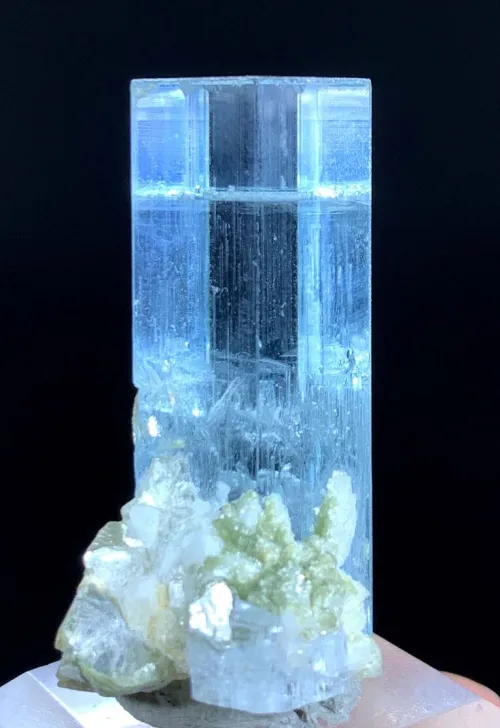

Through gemological observation, we see aquamarines show consistent but subtle patterns. Most natural specimens display weak to moderate blue fluorescence under long-wave ultraviolet light due to trace iron impurities within the crystal lattice. Short-wave UV exposure generally produces less pronounced reactions. Crucially, untreated stones tend to show more consistent fluorescence than heat-treated ones, where thermal processing may alter molecular configurations responsible for UV response.

Proactively verify claims by first examining stone treatments through documentation. Heated aquamarines often appear more uniformly blue but might show reduced UV activation. Natural samples frequently include slight color zoning which corresponds to uneven fluorescence distribution observable under magnification. Let this guide your inspection rather than anticipating spectacular displays.

Misconceptions persist that UV testing requires complex laboratory equipment. People often use weak consumer-grade UV lights in bright rooms, then conclude their aquamarine doesn't fluoresce when they simply lack proper observation conditions.

Laboratory protocols reveal critical setup factors: Optimal viewing requires darkroom environments that enhance detection of faint light emissions. Use UV lamps specifically emitting 365nm wavelength rather than broad-spectrum sources. Crucially, wear protective eyewear during testing since UV exposure poses eye risks unlike visible light inspection. The phenomenon occurs instantly upon exposure and ceases immediately when the UV source turns off, demanding focused attention.

Establish your testing regimen: First, allow eyes ten minutes to adapt to darkness. Position the UV lamp 10-15cm from stone at a consistent angle. Notice that transparent samples reveal clearer fluorescence effects than heavily included pieces - crystal clarity impacts visibility directly. Document observations using standardized descriptive scales ("inert" to "strong") rather than subjective judgments. For added precision, compare against known reference stones.

Variation between specimens leads some to question whether UV response indicates authenticity at all. Why might one aquamarine emit visible light while another identical-looking piece stays dark?

The underlying mechanisms involve structural differences: Iron impurities naturally fluctuate based on geographic origin and formation conditions. Brazilian aquamarines may show stronger reactions than Pakistani counterparts due to differing trace element concentrations. Crucially, the position of iron atoms within the crystal lattice affects photon emission - ions require precise configuration to produce visible fluorescence. Chemical impurities outside this specific arrangement typically absorb rather than emit light. Furthermore, significant color zoning in natural crystals can cause fluorescence patterns matching these chromatic bands.

Instead of expecting uniform fluorescence, train your observation: Compare stones from different regions when possible. Note that fluorescence intensity naturally varies geographically and doesn't correlate with Mohs hardness or durability. Remember, specimens lacking noticeable glow remain genuine aquamarines - fluorescence signals specific mineralogical conditions rather than acting as a universal authenticity marker.

People often hope UV fluorescence provides definitive identification, but many minerals show blue emissions. Aquamarine's value and unique sea-blue color mean it's frequently imitated by cheaper natural alternatives and synthetics.

Distinguishing features emerge under comparative analysis: Blue topaz typically remains inert to UV while certain synthetic spinels might show strong orange reactions absent in aquamarine. Glass imitations often display inconsistent bubbling patterns under magnification that don't correspond with UV-activated areas. Natural untreated aquamarine frequently maintains fluorescence stability across the stone unless disrupted by major inclusions or fractures altering light transmission.

Develop discernment through systematic inspection: Always combine UV observation with standard gemological tools like loupe examination for liquid inclusions common in natural beryl. When noticing fluorescence, ask: Does the pattern align with color zoning? Does documentation indicate treatments that reduce typical reactions? Such layered analysis creates reliable verification far exceeding UV testing alone.

Many dismiss UV fluorescence as mere scientific trivia without practical importance. Why should collectors bother with specialized lighting for an already beautiful gem?

The applications extend beyond identification: Historical verification often leveraged fluorescence characteristics since treatments altering trace element distribution didn't exist before the 20th century. Modern lab reports deliberately document fluorescence intensity, making it one of many origin indicators. Display considerations also matter - placing aquamarine near unfiltered sunlight for extended periods may theoretically impact long-term fluorescence stability, prompting museum lighting to incorporate UV filters.

Integrate these insights: First, obtain gemological reports that document fluorescence characteristics as baseline references. Second, avoid prolonged direct sun exposure for display purposes not due to damage risks (minimal thermal emission occurs during fluorescence), but to preserve optical properties. Lastly, recognize fluorescence as one strand in evidence-based appreciation rather than the gem's defining quality.

Among collectors, persistent questions emerge around fluorescence perception. "If it glows, isn't that radioactive?" reflects dangerous confusion between luminescence types. Others worry visible UV response indicates fragile stone integrity or artificial treatments.

Scientifically speaking, fluorescence differs completely from radioactivity: The phenomenon involves electron excitation rather than atomic decay, posing no health risks and leaving the material unchanged. Thermal emissions remain negligible during UV exposure, eliminating damage concerns. Additionally, absence or presence doesn't automatically indicate treatment - heated stones tend to show reduced fluorescence, but natural variations exist. What matters is understanding fluorescence origins rather than forcing interpretations.

Assess stones holistically: Remember fluorescence patterns complement rather than replace traditional assessment methods like refractive index testing or spectroscopic analysis. Document observations objectively, noting phrases like "moderate blue reaction" instead of vague descriptors. Recognize UV responsiveness constitutes just one fascinating aspect among aquamarine's inherent properties.

Understanding UV fluorescence transforms how you examine gemstones: The core principles center around recognizing variable expression patterns and using controlled testing conditions. Notice how impurities interact with crystalline structures rather than expecting simple visual spectacles. Practical application means using UV as a nuanced data point in broader identification strategies.

Begin simple: When encountering aquamarine claims, always ask about geographical origin and treatment history first since these strongly influence fluorescence characteristics. Prepare for testing with appropriate equipment - even reliable pocket 365nm UV lights produce better results than smartphone accessories. Most importantly, recognize that true expertise builds through patient comparison: Observe multiple stones under identical conditions to calibrate your perceptions.

Progress comes through incremental refinement: Next time you examine aquamarine or similar materials, first check two critical aspects: stone transparency and UV wavelength used. Transparent specimens tend to reveal fluorescence most clearly under 365nm long-wave light. Compare impressions against basic origin information - untreated stones from iron-rich deposits often show characteristic responses. With each observation, you'll build layered understanding that transforms confusion into grounded knowledge.