The naming stems from its seawater-like color properties, created by trace iron in beryl crystals. Remember this core principle: Aquamarine's identity is defined by its mineral composition rather than ocean origin, with visual perception playing a vital role in its naming heritage.

When encountering aquamarine jewelry or descriptions, many notice its oceanic references and assume a direct connection to seawater origins or maritime symbolism. Confusion often arises when seeing color variations in different lighting, hearing marketing terms like "ocean-blue gem," or encountering myths about saltwater formation. These impressions stem from literal name interpretations and superficial visual associations. This guide examines the geological and optical realities behind the name. We'll explore mineral composition factors influencing color, investigate light behavior creating water-like effects, and trace historical naming practices. By breaking down five key aspects—including how gemologists evaluate quality and why certain source locations yield distinct hues—you'll develop a science-based framework to independently interpret gemstone characteristics beyond poetic names.

People frequently describe aquamarine as "capturing ocean tones," assuming its naming originates from direct seawater properties. This interpretation emerges naturally because "aqua" means water and "marine" references the sea, while the gem's blue-green spectrum evokes coastal imagery. Advertisements reinforcing romantic watery associations further cement this perception.

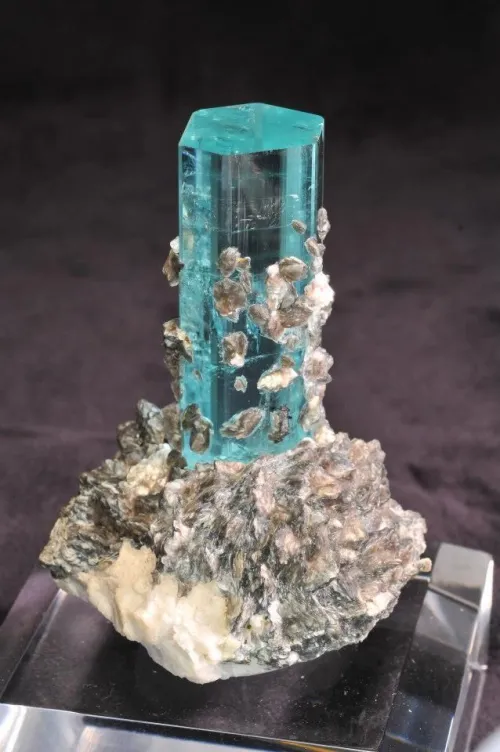

In reality, the coloration primarily results from trace iron within beryl structures during crystallization. Though iron impurities are crucial, their distribution patterns and charge states create color variations across specimens. Scientifically speaking, light absorption peaks around 427nm and 688nm wavelengths produce the signature blue-green visuals. More concentrated iron tends to deepen greens, while balanced levels achieve the ideal sky-blue associated with ocean namesakes.

When examining gemstones, notice how crystalline geometry impacts light paths. Next time you view stones labeled "aqua," focus on whether blue tones appear uniform at multiple angles. Genuine iron-based hues typically maintain consistent saturation regardless of rotation – unlike dyed imitations that show color concentration points.

Many intuitively judge aquamarine quality by oceanic blue intensity, assuming deeper saturation implies superior value. This belief stems from marketing images showcasing vivid specimens alongside watery landscapes, creating subconscious associations between color darkness and premium status.

A clearer perspective incorporates multiple technical considerations simultaneously: Iron distribution uniformity matters more than darkness alone, while cut precision significantly influences light performance. Well-faceted stones with 40%-60% pavilion depth often exhibit superior brilliance. Moreover, durability requirements like its 7.5-8 hardness ensure pieces resist scratches during wear, and thermal conductivity helps identify synthetics during professional testing.

For your own evaluations, start with brightness observation: Hold stones against neutral backgrounds and rotate them slowly. Quality crystals reflect light consistently across facets without dark patches. Additionally, inquire about origin specifics since Brazil's Santa Maria mines produce distinct blue tones compared to African greenish varieties.

Observers often report "water-like" movement within aquamarine, interpreting internal reflections as literal liquidity. Photographs capturing turquoise flashes under sunlight reinforce optical illusions suggesting fluid interiors linked to ocean naming.

This phenomenon owes to refractive behavior: Light interacting with hexagonal crystal structures bends at 1.57-1.58 RI, creating visual depth. Optimal faceting then manipulates this light through careful angular arrangements, where crown angles between 35-40 degrees produce that signature "pool effect." The interplay of refraction angles with natural inclusions may scatter light randomly, evoking sunbeam patterns underwater.

To demystify the "watery" appearance, examine stones under varied lighting. Notice how colors shift from pale blue in daylight to greenish in warm artificial light? This demonstrates hue dependency on illuminants rather than liquid content. Keep this principle in mind while shopping: Always request viewing under multiple light sources to assess true optical stability.

Some speculate aquamarines form in marine environments due to their name and color, imagining oceanic mineral absorption during crystallization. Such misconceptions arise when sellers reference "sea-born gems" or display stones with wave-pattern inclusions symbolizing watery origins.

The foundational geology reveals contrasting truth: These beryls crystallize in pegmatites and hydrothermal veins, requiring specific pressures and temperatures inaccessible to seawater. Volcanic heat sources near continental margins drive mineral-rich solutions into cavities where slow cooling permits crystalline growth. Crucially, iron must infiltrate during this phase to generate blue tones, as subsequent exposure leaves chemical compositions unchanged. While coastal mining occurs (like Namibia's deposits), seawater contact happens during extraction rather than formation.

Remember to prioritize verified reports over symbolic associations. When sourcing information, favor geological terms like "pegmatite-derived" or "hydrothermal origin" instead of poetic descriptors. These scientific indicators reliably confirm terrestrial formation regardless of extraction locale proximity to oceans.

Ancient narratives often claim sailors carried aquamarines believing the stones contained seawater spirits offering protection, justifying the ocean-related naming through folklore. Renaissance gem classifications like Agricola's writings strengthened this perceived maritime connection through mythical properties.

Linguistic archaeology provides more reliable insights: "Aquamarine" entered scientific terminology in the 1600s through German mineralogists describing "aqua marina" beryls, formalizing what jewelers already called "water emeralds" to differentiate them from land-mined greens. However, their mineral composition remained identical to other beryls, with color variation alone dictating nomenclature. While historical usage patterns suggest symbolic associations with water safety, gemologists note that cutting techniques only emphasized light performance – not watery spirituality.

When engaging with historical claims, contextualize them through mineral science timelines. Pre-18th century texts often blended gem mysticism with early observations. Modern confirmation requires cross-referencing stories with known optical properties. For instance, alleged "protective traits" originated from misinterpretations of its 7.5 hardness preventing breakage during travel.

Persistent assumptions suggest the ocean name proves aquamarine obtains its color from seawater minerals or that all blue beryls automatically qualify as aquamarines. These misinterpretations arise from oversimplified educational materials conflating descriptive naming with causal origins, alongside inconsistent trade terminology for pale varieties.

Reality centers on gemological definitions: The 1912 international standard required specific silica-beryl structures with iron-induced blue-green color to use the designation. Crucially, this naming reflects human perception and market tradition rather than oceanic interaction. Additionally, stones outside the defined hue range become "blue beryl," not aquamarine – a critical industry distinction validating the naming's visual rather than geographical basis.

Practice distinction checking through hue comparison: Carry a reference card showing certified aquamarine's defined color spectrum. When assessing jewelry, compare its hue to standard swatches before assuming oceanic naming applies. For online purchases, request videos showing movement across varied backgrounds since pure blues without green undertones may indicate mislabeled specimens.

Mastering three evaluation priorities allows independent verification beyond naming conventions: First, consistently examine light behavior rather than relying on catalog descriptions – stone movements revealing shifting blues/greens indicate natural origin. Second, prioritize documentation listing chemical composition percentages, particularly iron concentration levels validated through spectroscopic testing. Third, cross-reference source mines against regional characteristics; Brazilian materials typically show deeper blues while Pakistani specimens trend greener.

Build experience through incremental observation: Next time you encounter aquamarine, whether in photos or jewelry displays, apply the hue stability test first. Notice color consistency during rotation and lighting changes rather than focusing on saturation comparisons. By anchoring judgments in these observable interactions between gem structures and light physics, you transcend marketing narratives tied to oceanic imagery. Consistent practice develops your ability to recognize authentic mineral signatures independently.

Q: Does seawater contact enhance aquamarine's ocean-blue color?

A: No submerging gemstones in water doesn't affect their coloration, which depends on iron content locked within the crystal lattice during geological formation.

Q: Why do some aquamarines appear more green than blue in photographs?

A: Lighting temperatures can influence perceived tones dramatically – daylight emphasizes blues while incandescent lights may shift perception toward greenish spectrums. Also, iron distribution variations tend to create this visual effect.

Q: Can polishing technique or setting metal choice change water-like appearance?

A: Yes, specific faceting patterns maximize internal reflections that amplify "liquid" illusions. Additionally, platinum or white gold settings may enhance blue perception compared to yellow gold, which introduces warmth altering color balance.